Careers in Audit: The Hidden Risk of Professional Deformation

By Mikhail Ben Rabah, CIA, CFE, CRMA

Government Audit Manager, Presidency of the Government, Tunisia

Throughout my career in government auditing, I have met hundreds of auditors who never left the profession even for a short period. Some have been in the audit field for more than thirty years and have never been employed in management occupation

For many, it was simply their choice. Is this an issue? Not necessarily, but it could be.

It is a common belief that overall, people who never opted for a career change are those who demonstrate a strong commitment to their profession. Furthermore, the experience they acquired throughout their careers may be so valuable for their organizations. Although this is generally true, getting stuck in an audit job could not be the best career pathway for an auditor. Here is why.

Professional deformation, also called nerdview is “a tendency to look at things from the point of view of one’s own profession or special expertise, rather than from a broader or humane perspective”- Wikipedia.

Since the audit profession is too specific in the sense that auditors are required to maintain curiosity and professional skepticism all the time and consider fraud risks when performing all types of audit engagements, the risk of professional deformation arises. I was always told that auditors are used to suspect everything and everyone.

Although this may appear excessive and unreasonable, especially given that the audit mission is anything but “watchdogging”, many auditors have fallen into the trap. Not all auditors have developed the set of competencies required by the profession standards which make them less vulnerable to “professional distortion”. Likewise, not all audit departments are complying with profession standards.

For example, the IIA Global Internal Audit Competency Framework which outlines the core competencies recommended for internal auditors, emphasizes the need of positive communication and collaboration with auditees.

I love the part of this framework where it is clearly stated that auditors should balance diplomacy with assertiveness. Indeed, by gaining a better understanding of each other’s perspective and business acumen, auditors minimize the risk of professional distortion.

One of the implications of developing a professional deformation is that you may find it hard to take management responsibilities while planning to make a career change.

I have seen many auditors who failed to perform management jobs because they were still acting as auditors. Their management style was lucking flexibility, fast decision-making and acting, effective problem solving and insights.

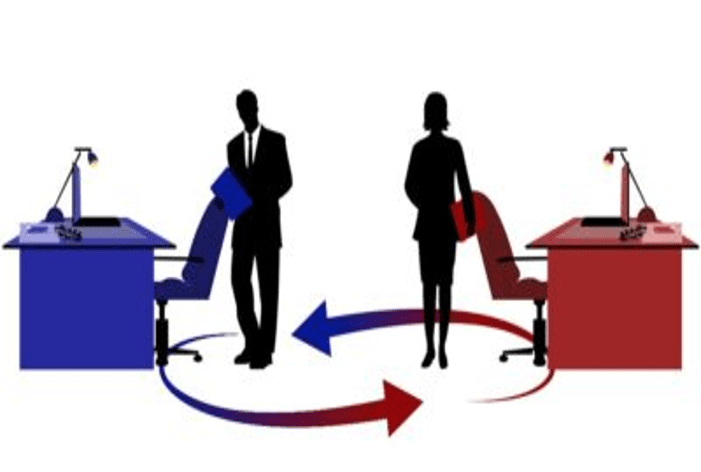

Therefore, it will be wise for both auditors and organizations to alternate audit and management occupations. It will help auditors better understand the management context and all types of constraints it brings. Nothing beats practical experience of management.

Some audit departments, especially in government have implemented this practice by promoting occupational mobility. Auditors are encouraged to take management roles within or outside their organizations.

Other organizations have opted for rotational recruitment programs as a talent management strategy. Rotational programs can be outbound or inbound. Outbound rotational programs rotate internal auditors out of internal audit and into other business units which gives them the opportunity to enhance their business knowledge in other functional areas.

Nevertheless, while opting for occupational mobility or rotational programs, organizations should always be aware of potential conflict of interest that can arises when assigning management roles to auditors.

The management occupation should never be in conflict with the previous audit role in accordance with codes of ethics and professional standards.

Auditors, do not hesitate if you are tempted by a new experience in a management role.

- Shall internal auditors be prepared to “Metaverse”? - November 6, 2021

- Overzealousness, a Threat to Auditors’ Objectivity? - January 19, 2021

- How Worthy Time Management is in Internal Auditing - December 28, 2020

Stay connected